Pray Away, a 2021 documentary now showing on Netflix, is not a movie one can just sit down and leisurely watch. If you grew up queer and Christian, like me, it’s difficult and brings back more than a few hard memories.

It is also a hard crash course on the last 40 years of the American culture wars, and an insight into where conversion therapy stands today. It’s a story of the limits of human endurance, and the struggle to find acceptance, ourselves, and our community.

For years, I’ve heard the horror stories of conversion therapy, experienced by an estimated 700,000 Americans today. Conversion therapy is a process to change one’s sexual orientation or gender identity that is now considered to be abuse by most psychology and mental health experts. It can include barbaric, crude attempts to change a person through electroshock treatments, or can be physical, verbal, or emotional abuse.

This is not that story.

Pray Away is about how conversion therapy is still happening today and masquerading as religious love.

The tragedy of conversion therapy is not only that it doesn’t work (more on that later), but that it sets people up for failure. And that failure can be emotionally devastating: Those who have experienced conversion therapy are more than twice as likely to think about or attempt suicide., the Williams Institute reports.

On the surface, the conversion therapy featured in Pray Away seems benign and innocuous. But nothing could be further for the truth.

In this film, we see conversion therapy as a combination of a revival, group therapy, faith healing, testimonials, and prayer. The gatherings we see are not much different from standard evangelical worship services – except they’re talking only about changing sexual orientation or gender identity.

It’s around this time in the movie that I experienced flashbacks. I began to recall all the theology that 10 years of private Lutheran schooling in the 1980s had instilled in me. For my entire education, I attended a Christian school. This was during the heyday of Exodus International, and an era of “Satanic Panic,” where everything secular was evil.

I was taught that all of humanity has fallen from the grace of God. That in the words of the Nicene Creed, “I confess that I have sinned against you in thought, word, in deed.” Essentially, I was taught, everything is a sin, but everything can be fixed with enough faith.

A lot of religious leaders in the 1980s labelled popular culture as a gateway to the occult. I remember one of my pastors’ sons telling me Led Zeppelin was satanic. My response was, “Have you ever listened to any of it? Stairway to Heaven is song about the choices we make in life.”

It was the premise that “everything is evil” that led to the founding of Exodus International, the key conversion therapy group featured in Pray Away.

Exodus co-founder Michael Bussee, who helped start the group in 1976, recalled how back then, there were support groups for helping Christians cope with alcohol addiction, drugs, and marital problems.

He asked himself, “Why wasn’t there any groups helping people cope with same-sex attraction?” From there, he formed a support group that became a template for groups all around the country.

Bussee didn’t remain in the group for long; he personally learned that trying to change one’s sexual attraction is impossible. He left the group in 1979 to form a long-term relationship with Gary Cooper, another Exodus member. “I left because I wasn’t changing. The people around me weren’t changing. This wasn’t working.”

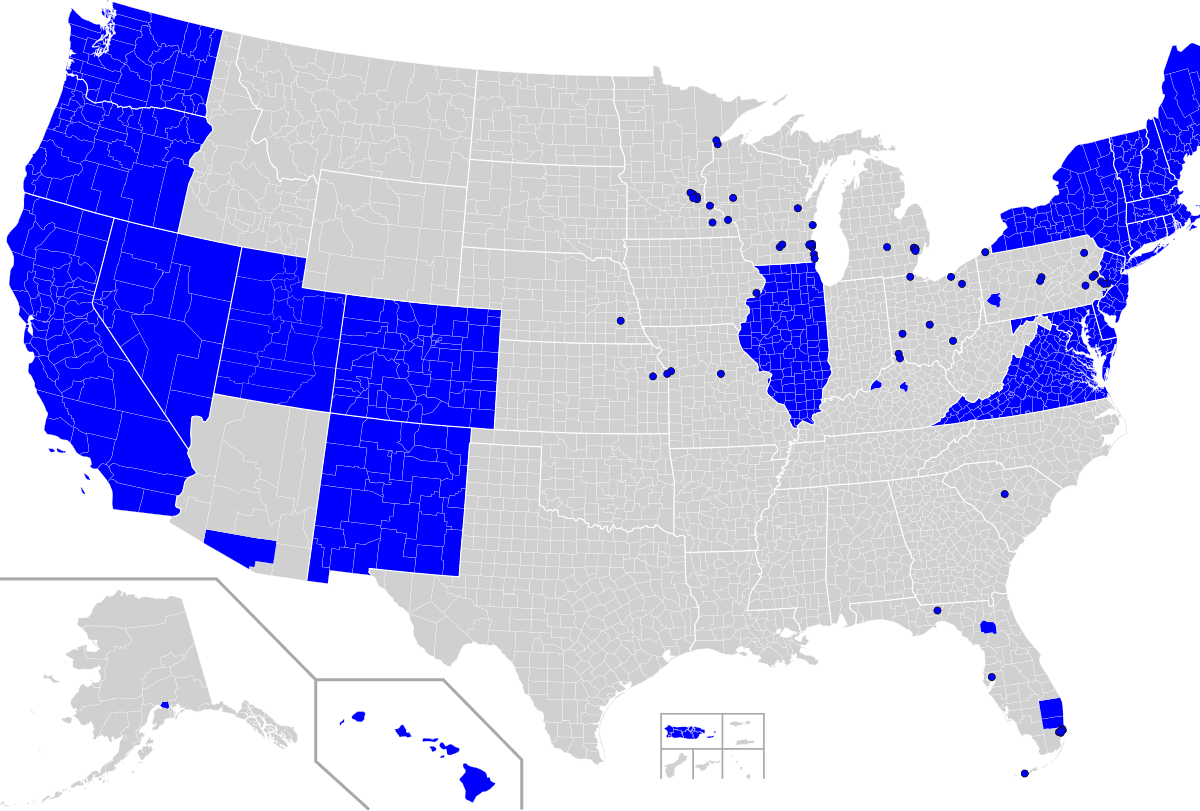

But by that point, Exodus International had become a national political force.

As skeptical of the Christian faith as I was, even I could not escape questioning my own sexuality and gender identity while growing up. No one was gay in small-town Iowa. “Being gay” was one of those things people did on the coasts, the focus of derisive whispers here.

In catechism classes, the pastor would say, “As Christians, we have to love gay people.” The unsaid part of that sentence was “…if they change.” Portrayals of homosexuals in sermons and media were always negative.

No wonder I had a crisis of faith at age 13. I kept hearing from my church and school leaders that gay people could not go to heaven, but I also knew in my bones that I was a transgender person. I knew that every fiber of my being told me I was a girl, forced to live for now as a boy, and that femininity was as natural to me as breathing.

Feeling alone, isolated and unable to accept the truth, I found I couldn’t hold onto faith. But I still could not yet embrace myself. I could only try to be straight by doing “straight things” like getting married and having a family.

Human beings are survivors, and difficult choices should be looked at through that lens. My approach was this: “If I can’t have everything I want, I’ll do what can I to survive and keep the world from crashing down on me.”

That sentiment is felt as Pray Away drives on.

John Paulk, who was once known as the most famous ex-gay in the world, had much the same idea I did. He tried to have a family. “I was on a mission, a relentless mission to find a wife and have a family,” he says in the film.

But he left Exodus after getting drunk one night, ending up in a gay bar in Washington, D.C., and being publicly outed. He is now in a long-term relationship with another man and talks in the film about how he hurt people through Exodus. “[I] caused people to think there was something wrong with them. Because they’d look at me and say, ‘If he’s not attracted to the same sex, there must be something wrong with me.’ ”

Julie Rodgers, another former Exodus leader, shares in the film how she came to her mother and was immediately introduced to an Exodus activist. “I didn’t know if I could be straight,” Rodgers tells us. “But I thought there was a path to being a true believer, and I took it.”

She recalls attending Exodus youth retreats that were supposed to help participants overcome their same-sex attractions, often through strictly enforcing gender roles. Even in that environment, Rodgers recalls, moments of honesty shone through.

“Hanging out late at night after counselors had gone to bed, we got to be our little queer selves. It was one of the few safe places, because it was an Exodus International conference. But that is what belonging looked like to us.”

Julie would later go on to be part of Exodus’ ministries and speak at their conferences. But in 2013, she and other Exodus leaders sat down face to face with Exodus survivors – people who had left the organization and stand against it now.

The footage captured by Lisa Ling on her show “Our America” was devastating. And the experience triggered something in Rodgers. “I felt like I should be on the other side of the circle,” she shared years later, after she’d married a woman she loved.

The sharings of Bussee, Paulk and Rodgers reminded me of my own path to self-acceptance. I, too, took many long twists and turns, including thoughts of suicide. I found myself so I could be a parent to my son.

The Lisa Ling airing also led Exodus International to close its doors. And the vast majority of studies on conversion therapy are inconclusive, reports Cornell University: 13 of those 47 studies show conversion therapy does not work, and only one indicated it can work.

Still, as the move shows so well, conversion therapy hasn’t ended. “Pray Away” opens with the anti-transgender conversion therapy group Freedom March.

The film shows Freedom March founder Jeffery McCall, a self-described former transwoman who leads Freedom March’s anti-transgender efforts. McCall reminds us that so many stories don’t have the happy endings of Rodgers, Paul, Bussbee and other survivors.

Watching a room full of Freedom March members sing “We are the warrior,” while simultaneously seeing the blank and far away look on McCall’s face as the music plays, is yet again, devastating. I recognize the look on his face as the same look I had staring back at me for 15 years, before I accepted myself.

That’s the reality of watching Pray Away. You will feel overwhelmed. But it’s important to watch it. It’s important to understand conversion therapy is still happening, know what it is when we see it, and prevent others from lifetimes of misery and heartache.

(You can find Pray Away on Netflix. Click here for more information.)

(cover photo by Ivan Radic, Flickr)