Thirty-two years ago, I broke my neck training for the AAU Junior Olympic Nationals in gymnastics. At age 15, I suddenly found myself paralyzed from the chest down, a quadriplegic navigating the world from a manual wheelchair.

When it was time to come home, my parents realized something that far too many American families still face: our home wasn’t built for me anymore.

My childhood bedroom was upstairs – nine steps up and thick with carpet. The only bathroom was on the top floor, and the only way to even enter the house was up three stairs.

We couldn’t afford to buy a new home, much less a ranch house in our area. And we certainly couldn’t afford the steep price of retrofitting everything. So we had to make tradeoffs.

My father, who was dying of cancer at the time, built a ramp himself. As a former professional fence builder, he had the skills, but not the energy. He never once complained, but I could see how hard it was for him.

Friends and neighbors fundraised to help install a platform lift so I could access the basement, where I’d now live. A chairlift wasn’t an option; I couldn’t transfer out of my chair, so we needed a full platform that could carry me and my manual wheelchair together. Even back then, the cost of these lifts was jaw-dropping – about $1,000 per stair.

We had to decide which parts of the house I’d be allowed to access — based not on my life, but on our finances.

It’s been over three decades since that homecoming. And still, 99% of homes in the U.S. are built with doors too narrow for a wheelchair, wrote the Urban Land Institute in 2023. It doesn’t make sense – not economically, not ethically, not practically.

What Visitability is, and Why It Matters

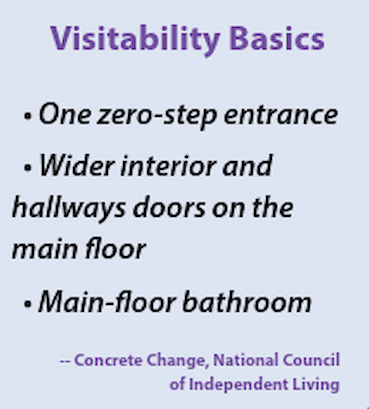

Visitability is a housing design approach that requires three simple features in newly built single-family homes:

- At least one no-step entrance on the main floor

- Main floor doorways and hallways at least 32 inches wide

- A usable bathroom on the main floor

That’s it: no elevators, no expensive lifts, just basic, thoughtful design. And yet, so few municipalities have adopted it as a standard.

In Bolingbrook, Ill., where I now live, we passed a visitability ordinance over 20 years ago. Every new single-family home built since must include those three features. The ordinance was adopted unanimously by the village board because our leadership understood that true inclusion means making everyone feel welcome, without having to ask.

Today, Bolingbrook has more than 4,600 visitable homes, representing over 25% of our single-family housing stock. That’s one in four homes with basic, no-barrier access. Not just for people like me, but for aging parents, young families with strollers, friends with broken legs, and workers hauling deliveries or furniture. It helps everyone.

That’s the curb-cut effect in action. And yet, when I’ve tried to help bring visitability standards to other towns, I’ve encountered baffling resistance — most of it based on aesthetic concerns. People worry that no-step entries “won’t look nice.” But who are we designing for? The illusion of perfection, or the reality of people’s needs?

The Human Cost of Inaccessible Housing

While more minor modifications (ramps, grab bars) may cost just a few thousand dollars, major overhauls – including lifts, complete bathroom reconfigurations, and structural changes – can reach high five figures to six figures in some cases. Most families can’t afford that. So they compromise.

They isolate loved ones to one floor. They limit family gatherings to places with ramps. They carry their children or elders up stairs until their backs give out. Or they move, leaving behind support systems, neighbors, and homes they love.

I know multiple people who had to leave their longtime homes once they developed mobility challenges, simply because the cost of modification was too high.

One of those people is my own mother. After a recent knee replacement, she’s now struggling in her beloved three-story townhome. She doesn’t want to leave, but she has no choice. One of my kids even moved in with her so she wouldn’t be sent to a care facility.

But the writing is on the wall: she’ll soon have to sell and find a ranch house just to maintain basic independence.

Meanwhile, as of 2024, 12.2% of U.S. adults (about 32 million people) live with a mobility disability involving serious difficulty walking or climbing stairs, according to the CDC.

That’s not a fringe group. That’s a massive segment of our population who often can’t find homes they can safely enter, live in, or even visit.

Let me say that again: millions of Americans are excluded from housing not based on income, but on the presence of stairs.

Opportunity Lives Where Access Does

Housing is about more than shelter. It’s where opportunity begins, where families gather, where neighbors connect, where holidays are shared. It’s the bedrock of community. And that’s why visitability isn’t just about physical access; it’s about dignity, connection, and participation.

When I was excluded from Thanksgiving at my in-laws’ home because no one could carry me over the steps anymore, I didn’t just miss dinner. I missed stories, laughter, and moments that never come back. My presence became a problem to solve, not a given to plan for.

That’s the hidden cost of inaccessibility. It doesn’t just break budgets, it breaks bonds.

The Economic Argument

Visitability isn’t expensive. According to the National Council for Independent Living (NCIL), adding visitability features to a home during construction costs $100 to $600.

Compare that to the cost of retrofitting later. The math is obvious. The return on investment is undeniable.

More than 20 percent of households are projected to have at least one disabled resident by 2050, the American Planning Association estimates. So why aren’t we building smarter from the start?

A National Mandate for Common Sense

We have a blueprint for success. Bolingbrook proved it works. Other towns can follow suit—if we have the political courage and civic will.

It’s time for federal and state governments to:

- Offer tax credits and grants for visitable home construction

- Update building codes to require basic access in new construction

- Include disabled advocates in planning decisions

Let’s stop building homes that lock people out and start building homes that welcome people in.

Inclusion Begins at Home

We often talk about independence in this country – about liberty, about the American Dream. But what good is liberty if you can’t get through the front door?

Visitability isn’t about building for “them.” It’s about building for all of us – our future selves, our families, our neighbors. It’s about refusing to accept that a person should have to choose between access and belonging.

I chose Bolingbrook because it gave me the chance to live, not just survive. For the first time in my life, I could visit my neighbors without needing to ask for accommodation. That’s not a luxury. That’s what home should be.

Let’s build a future where everyone can come home.