The city of Des Moines intentionally undertook policies in the 1930s and 1960s to limit housing options for Black residents, writes a University of Iowa student.

In addition, writes Ross Clowser, the city’s failure to clean up areas deemed by the EPA to be contaminated with toxins have hit Des Moines’ Black residents harder than the general population.

As a result, living in Des Moines can be as hard for a Black person as living in some of the nation’s most segregated communities, Clowser writes in a 2018 paper he is reviving in light of the protests happening nationwide following George Floyd’s May 25 murder.

“Des Moines suffers from similar patterns of systemic and institutional racism, resulting in the same predictable inequitable socio-spatial outcomes we see in places like LA, New York, and Chicago,” Clowser writes.

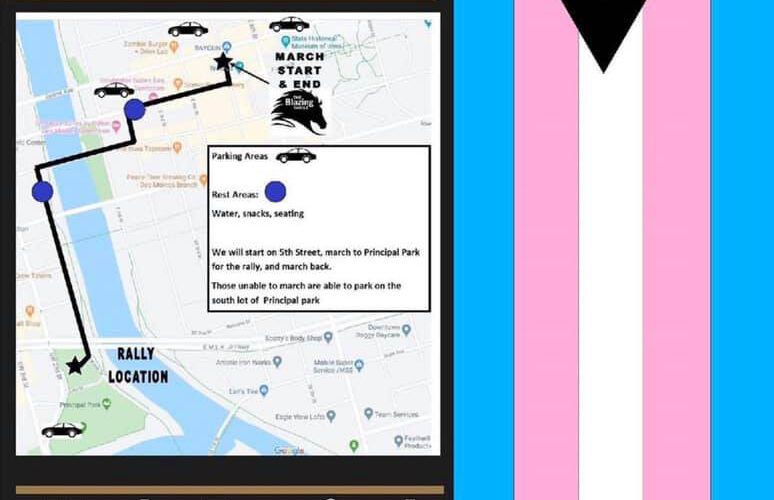

The U of I grad student is releasing his 2018 paper anew as Des Moines’ Black Lives Matter movement grows along with other BLM movements nationwide. The Des Moines group will protest again today with a list of demands that starts with “abolishing the Des Moines Police Department.”

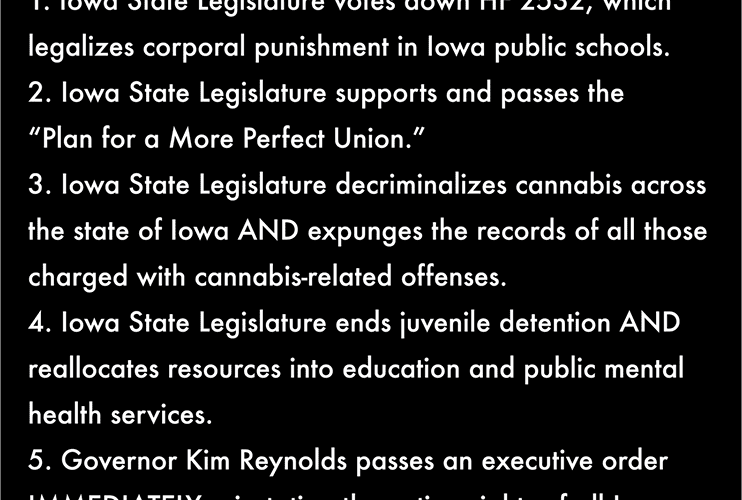

In addition, the group is focusing on the Iowa State Legislature, asking for statewide changes that include:

• laws that impose a statewide ban on police chokeholds and the rehiring of officers who have been fired because of misconduct, and that empower the Iowa Attorney General to investigate charges of police misconduct

• an end to juvenile detention, with its funding shifted to public education and mental health services

• banning of “corporal punishment,” or punishment by physical act, in Iowa’s public schools

• statewide decriminalization of cannabis, and expungement of cannabis-related offenses from public records

• and the restoration of voting rights for felons, who are currently banned under Iowa law from participating in elections.

Clowser’s assertions are not new, especially as more people become more aware of systemic racism because of the articles, protests and interviews being conducted following Floyd’s death May 25.

But the statistics and documentation he has compiled help demonstrate the truth of systemic racism, and how earlier racist policies may have helped create modern-day dilemmas like the documented repeated devaluing of Black men at the hands of police.

Papers like Clowser’s help illustrate why many protesters are, like the Des Moines Black Lives Matter group, asking for more than an end to police brutality.

Among the key information Clowser documents:

• Des Moines was intentionally developed, earlier in its history, to limit where Black people could live, according to a 1935 housing report from the Iowa State Planning Commission that Clowser cites. The report suggested using low-cost housing as a way to create barriers so that ” … the negroes could be confined to more definite areas where they would have much less damaging effect upon the desirability of the property surrounding.”

• Des Moines’ once-thriving Center Street neighborhood, known as a core of Black business in the 1960s, was razed to make room for Interstate 225 in 1967, displacing many of the city’s Black residents, writes Clowser. “A family displaced by projects ongoing in Des Moines was five times more likely to be of color than white,” writes Clowser. He notes statistics showing that 867 families were forcibly relocated because of urban renewal projects in the 1960s — almost 30 percent of whom were black, even though Blacks accounted for only about 6 percent of the city’s population.

“This development devastated much of the Black community in Des Moines, removing its cultural core, economic center, and destroying assets, further sinking African American families into a generational wealth gap and forcing them into undesirable areas of the city,” Clowser writes.

• The tax base of Des Moines began to shrink in the 1950s because of “white flight,” the large-scale relocation of more affluent, white residents to suburbs, and has continued to struggle to present-day. This has meant fewer public resources to help Des Moines residents, while suburbs have gained more public resources. “Des Moines is ‘failing to successfully compete against its own suburbs for middle and upper class households who increasingly buy outside the city and, in spite of Des Moines revitalized downtown, live their lives outside the city,’ ” Clowser wrote, citing an official report.

• Affordable housing has dropped by 50 percent since 2000, writes Clowser, quoting the Urban Institute, which says the rate of affordable housing has dropped from 28 to 14 for every 100 low-income families. The units that are available often have severe problems like “black mold and severe water damage,” Clowser writes.

• Furthering these environmental disadvantages, people of color in Des Moines are far more likely than white residents to live within the “geographic plumes” of facilities labeled “hazardous” by the Environmental Protection Agency based on an index of toxin release. More than 30 percent of people who live within those “plumes” are people of color, compared to only 10 percent of residents outside of the plumes, Clowser writes.

(Cover photo, courtesy of urbandsm.com, is of Center Street in Des Moines in the mid 1950s)