Please help! Some people are in trouble, right now. They’re in danger. Call the first responders. Hurry! Mobilize the support.

Nope.

A few weeks ago, a group of organizations on the front lines of racial justice declared a “state of emergency for Black Iowans.” They cited numbers, recent events, history … And then we all moved on.

There has been little ongoing news coverage. No special projects. Few, if any, follow-ups. Hardly anyone is lifting a finger in response, so far.

The press release, endorsed by nine social justice groups and echoed afterwards by more such groups, calls Iowa out as a “sundown state.”

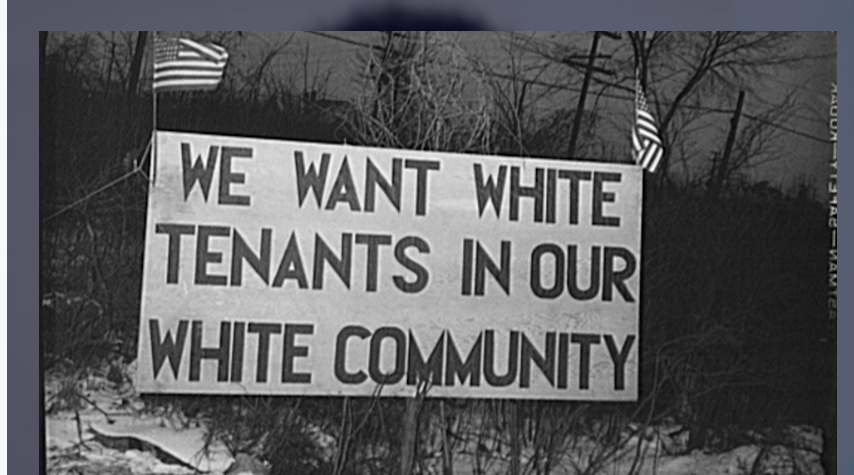

This phrase — also the centerpiece of “Lovecraft Country,” a new horror series by Misha Green and filmmaker/racial justice activist Jordan Peele — refers to actual signs that used to appear outside of towns throughout the Midwest and North, since before the turn of the century to as recently as 60 or so years ago. These signs warned Black people, in the least kind terms we will not repeat here, that they should fear being around that town after the sun goes down.

If they didn’t, they’d be escorted out of town by law enforcement, threatened with violence by an angry mob, or actually attacked. Sometimes, the mode of messaging wasn’t signs. It was an actual city ordinance — or the worst and most nefarious of all, word of mouth.

This feeling of isolation and constant threat is how Black community leaders say they and their fellow Black residents feel living in Iowa, even today. That people of a certain skin tone still feel downright unsafe here, that most of us live like we’re OK with that, is a terrifying thought, even if you are not Black. I cannot imagine the sense of “always on alert” that Black Iowans live every day.

Since May and June, we’re supposed to have taken that next step. We’re supposed to recognize that if our neighbors aren’t free and safe, none of us are. So we should all be freaked out by the fact that racism from Iowa’s past is still shaping its present.

But we’re not. The complacency remains, even after George Floyd, Ahmaud Aubry, Breonna Taylor, Elijah McClain, Jacob Blake, Daniel Prude (these are just the most publicized cases since February).

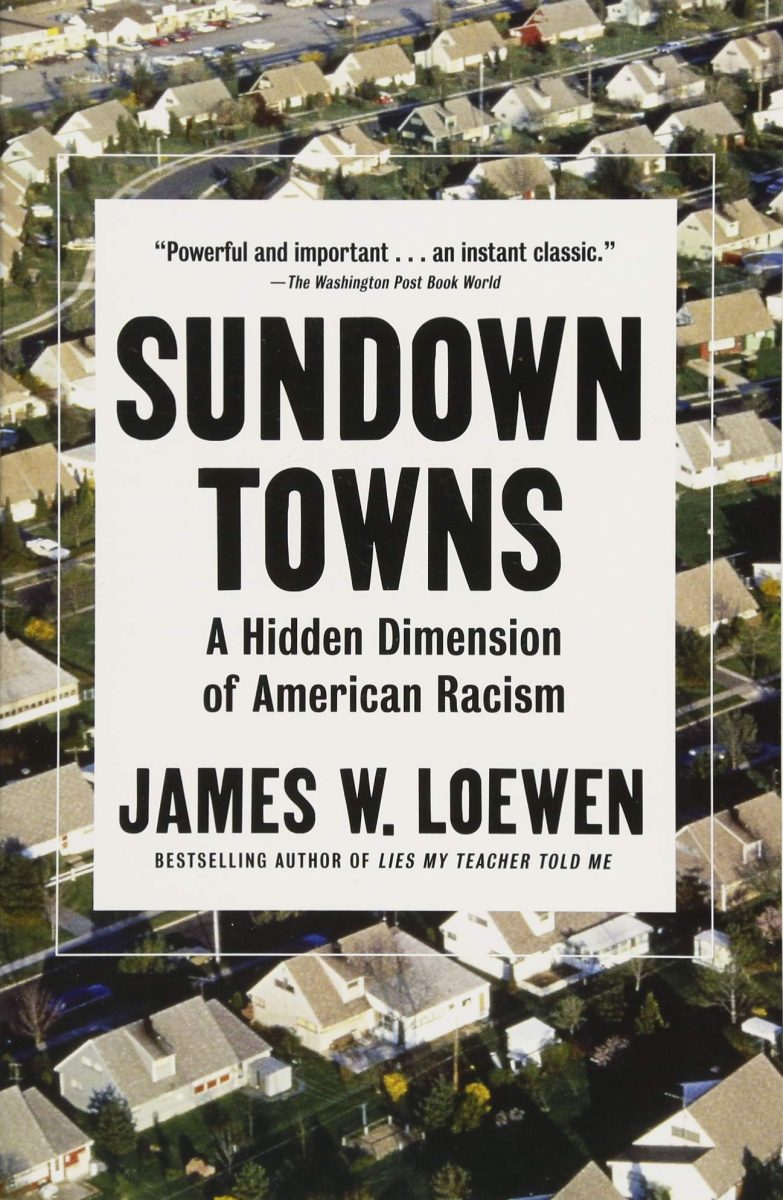

This alarm about “sundown towns” and their impact on the Midwest has been sounding for years, if not decades. In 2008, author James Loewen asked us all to focus on this dirty little secret of the Midwest with his book “Sundown Towns: A Hidden Dimension of American Racism.” It’s considered a groundbreaking reckoning with a shameful past.

Loewen lays out the past of sundown towns and also warns that discrimination can be tricky, with perhaps just one Black family allowed to live in town, or maybe some non-Black People of Color. The heyday of sundowns came right after the Civil War, Loewen writes, during a period of “backlash” against Black people for being freed from slavery.

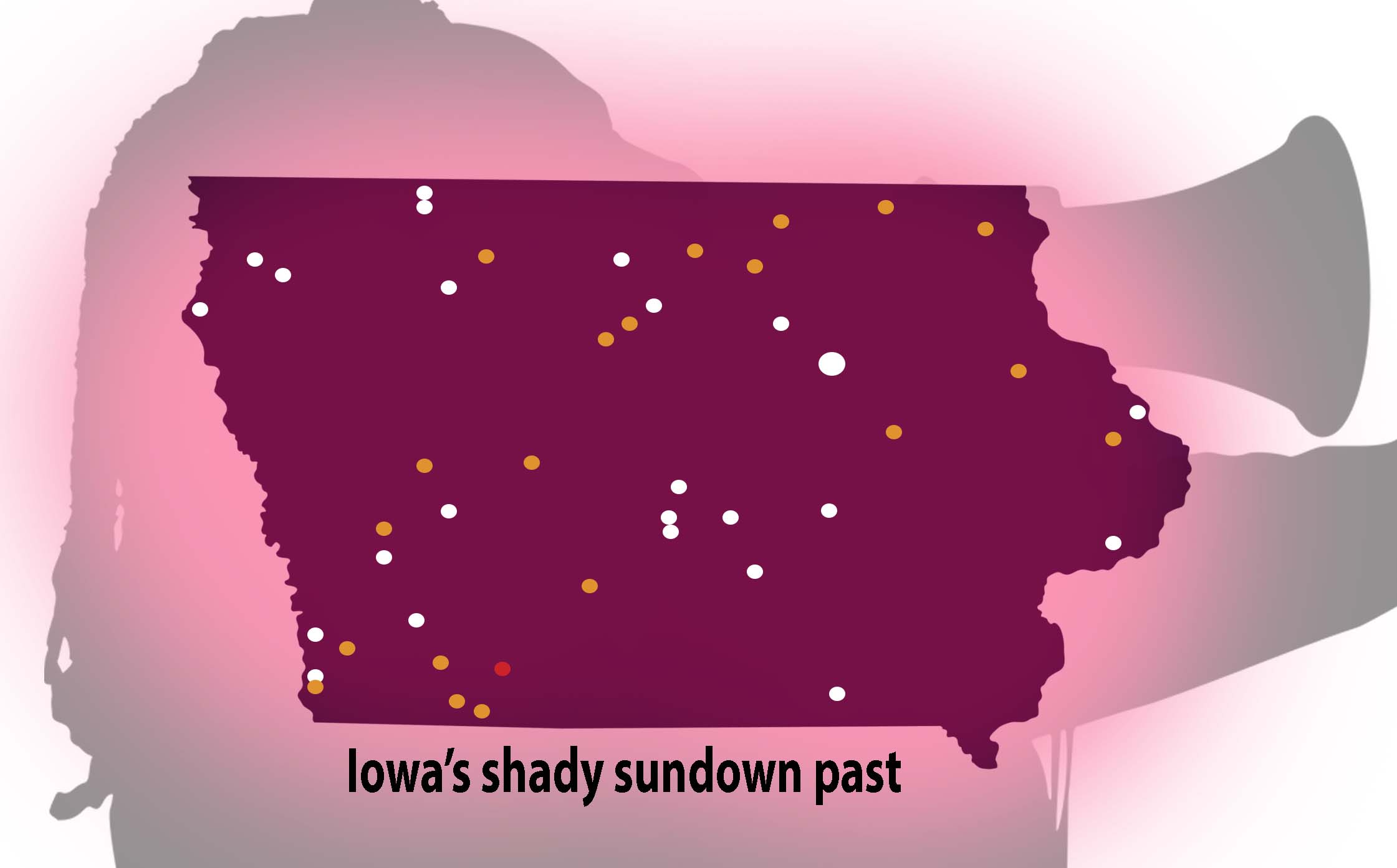

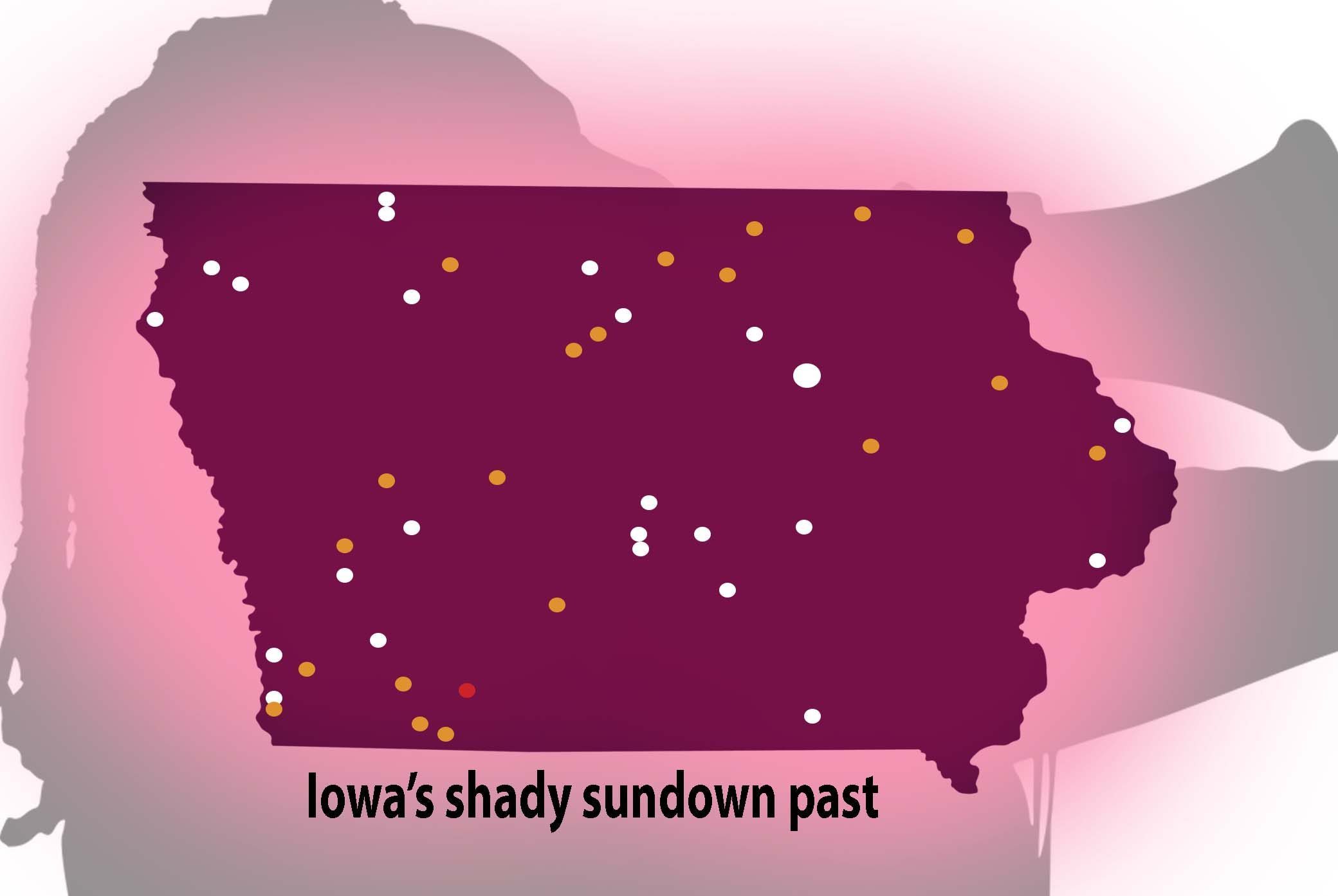

In Iowa, Loewen listed 40 possible, probable or confirmed sundown towns; they’re noted on the cover image, with possible sundown towns in white, probable ones in orange, and confirmed sundown towns in red. In interviews since 2008, he’s mentioned a possible 200 Iowa sundown towns. His information forces us to face the truth: Iowa is still super, excessively white in many places and has been for a long time. As Loewen points out, it takes more than chance to endlessly be a small community where you can count the number of non-whites on one or two hands. It takes intention.

Illinois, by the way, has an astounding 670-plus such towns, says Loewen. But while Illinois has a known history of racial tension because of urban Chicago, and the endless standoff between Chicago and “downstate,” Iowa is known for “Iowa nice.”

“With what are supposedly America’s friendliest people, it may be hard to believe that Iowa could have had such an intolerant past,” writes Nathan Davis for the Iowa Peace Network in 2013. But, he continues, “the actions of Iowan communities from 1890 through 1970 (possibly even today) has hurt the way that our communities have grown culturally, socially and ethnically.”

It’s why even today, Iowa’s most liberal bastions, like Iowa City, still feel unsafe to Black people, as guest columnist Latisha McDaniel Grife once wrote here in the pages of The Real MainStream.

“When I lived in Louisiana, the enemy was clear: areas with confederate flags were a clear indication that ‘my kind’ was not welcome,” she wrote in February 2019. “Iowa is a different animal: you don’t really know you have enemies until the cops show up.”

Since Loewen’s book in 2008, others have tried to pick up that gauntlet. Davis is one; another is Heather A. O’Connell, who wrote about them in her 2018 paper “Historical Shadows.” O’Connell says that sundown towns force us to acknowledge the advantages whites have had historically. Lyz Lenz, former liberal columnist for The Gazette, wrote about sundown towns last September, just over a year ago. “Iowa, you’re racist,” screamed the headline on her column.

Bryce Huffman also revisited sundown towns this year. Huffman talks on PBS about how sundown towns preserved privileges for whites. Many of them had business districts dominated by banks who followed racist lending practices that explicitly forbade Black customers.

“ … with a sundown town, it’s very purposeful,” he says. “It’s very much so that, ‘if you are a white middle-class family, we’re going to give you this house, even if the Black family that wants to buy it can pay us more money.’ “

Sundown towns are also at the very root of police brutality, of what scholar/activist Kesho Scott calls “inappropriate policing” to encompass oppressiveness that doesn’t involve actual brutality. Huffman brings this to life by describing marginalization in his account of traveling through Gross Pointe, a confirmed former sundown town, as a Black teen.

“If you live in a suburb that is 90-plus percent white, and you see a group of black kids driving through it, the police automatically look at them as outsiders,” Huffman says. “That actually is where a lot of the implicit bias against young Black men, particularly, comes from when it comes to law enforcement: ‘Huh, you’re in an area where historically you’ve never been. What are you doing here?’

“It automatically brings up suspicion. And instead of seeing me as someone who’s going home after visiting a friend, I’m someone who’s now seen as a suspect in some wrongdoing.”

Again, imagine the advantage white people like me have had all these decades, never having to drive around with that constant sense of isolation and unwelcomeness, except in terms of sexuality, which is not something that is all over every centimeter of our bodies like skin tone.

This is not just about the under-privileged and the mistreated; this is about the over-privileged. And guess what, white Iowans? That means most of us.

Yet still to this day, after all the horror of recent months and years of videos and revelations, a lot of whites still don’t “get it.” In McKinney Texas, for instance, the town’s only Black city council member tried to sound the alarm of the Black state of emergency there, after two fatal police shootings. He ended up facing a recall and being scolded for being disrespectful to police. Clearly, the long-term damage of sundown towns remains.

How do we finally respond after decades of entrenched indifference toward racism? How do we snap out of something that many of us don’t want to think about, let alone admit, in our Iowa nice bubble? Loewen lays out a pretty clear path. And like all “come to Jesus” moments, it starts with the hardest part: admitting it. Towns with any hint of sundown pasts need to step forth and acknowledge it; in Iowa, attention to the emergency beyond the week it is announced would be the first step.

Beyond that starting act of public confession, Loewen says to fight the racism of sundown towns by focusing on two power institutions, the ones that have the greatest impact on a community’s daily life.

Look at the teaching force, he says. And yes, look at the police force. If a town still, in this day and age, has overwhelmingly white teachers and cops, start there. Press for a more diverse workforce.

Huffman offers two other solutions:

• Community groups that represent residents need to join the push for diversity and fight racism where they can. Are neighborhood associations, local nonprofits, and other non-governmental organizations joining the press for more diversity? Are they asking the question, “Why does our neighborhood look this way?” Are they undertaking steps needed to ensure Black residents, Indigenous people and People of Color feel welcome?

• Secondly: LGBTQ people need to join the front lines! Huffman points to Ferndale, a confirmed former sundown town. “Now, Ferndale is seen as this very progressive liberal place where everyone is accepted, in large part because of their acceptance of the LGBTQ community,” he says. “I don’t know about you, but when I see a Pride flag, I feel a lot safer. Because I’m like, ‘If they like gay people, there’s a chance they don’t hate Black people. Just a chance.’ It makes me feel just a little bit more comfortable.”

We’re grateful to see that Iowa’s local media is doing such an amazing job day-to-day in its coverage of racial injustice and fighting systemic racism. A decade or so ago, perhaps the Black racial justice community leaders cry of “emergency” might not have earned more than a brief; this year, many major and alternative media covered the release.

We can do more ourselves, as the only LGBTQ-identified, intersectional publication in Iowa and Illinois. For example, though we’re excelling in the LGBTQ and women area — two identities also historically under-represented in media — we’re still a publication with a mostly white contributor force. And while our readership is diverse, it’s also still overwhelmingly white.

We need to be more a part of the resistance, less like the status quo.

How to make progress beyond the emotion-fueled protest spirit of May and June is hard, for all of us. We’re all feeling around, in a way, to figure out how we can fight systemic racism beyond protesting. After all, sundown towns sometimes work their evil in unspoken ways. We have to keep talking about this, to finally move away from the past.

As many wise people have said, the only way out of some things is to go deeper into them. Consider this our challenge to anyone reading this — especially if you’re white! — to go deeper. Don’t be afraid to confront our racist past and to keep confronting it.

Also consider this our commitment to follow through. This publication will be by your side in that journey, even if November’s election is the landslide in favor of Biden that many are hoping for to break President Trump’s divisive influence. It will be even more important to stay focused, to do what we all can, to heed the call for help, and to finally end this state of emergency for Black Iowans regardless of who is in office.

Keep supporting your local media, daily publications like The Gazette, The Des Moines Register, the Iowa City Press-Citizen, and the Quad-City Times, that are doing more than they used to toward recovery from racial injustice. Keep empowering your alternative media — not only this publication, but Little Village Mag, Iowa Starting Line, and other news sources working hard every day to shed light on the dark past, make it through the turbulent present, and do better in the future.

And then, go the extra steps offered by Huffman and Loewen. Start attending your local neighborhood association and ask what it’s doing to bring in more diverse residents. Start attending School Board and PTA meetings, ensuring the teachers and public school workers your kids (or your neighbor’s kids) see every day are clearly of all colors and not just one.

Heed the Emergency. It’s urgent! It has been, for more than a century.