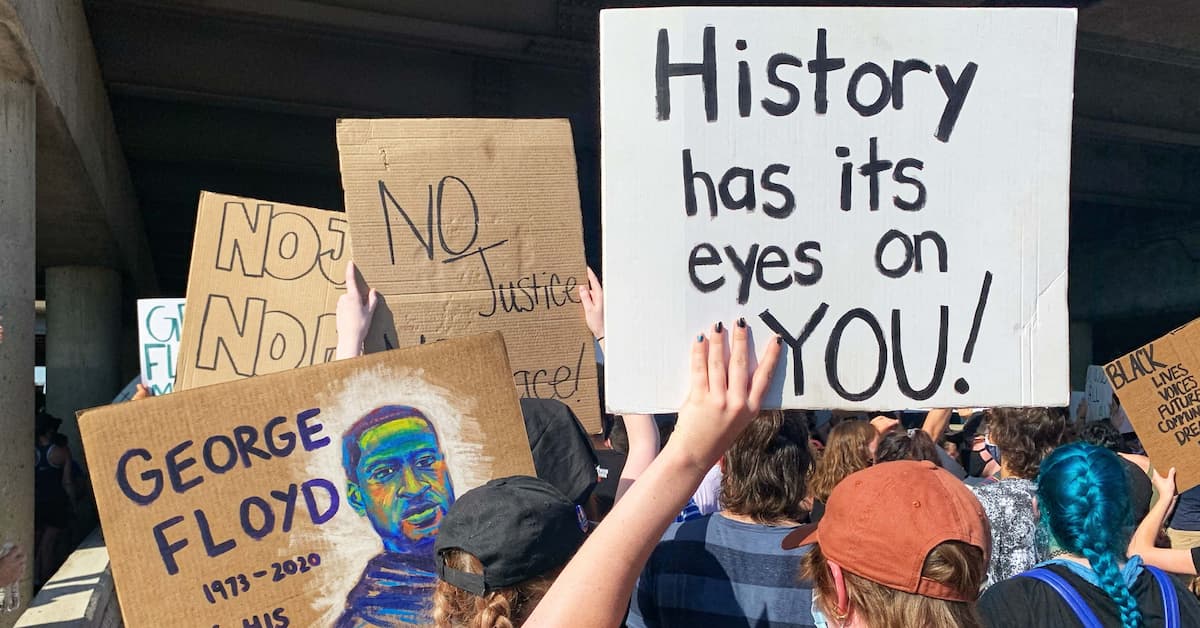

Days after Derek Chauvin’s trial resulted in full convictions last week for George Floyd’s murder, we’re in the thick, realizing things haven’t changed much in the past year.

Since Tuesday alone, victims of known videotaped police shootings are a 40-year-old unarmed Black father of 10 wanted on drug charges, shot in the back; a 21-year-old unarmed Black father of one wanted for missing a Zoom hearing on gun charges; another 21-year-old unarmed Black man who sought help from police; a 16-year-old Black girl shot from behind while rushing another girl with a knife; a 13-year-old Mexican boy shot after running down an alley from police, . In prior weeks, video emerged of an unarmed Black Army lieutenant stopped, terrorized and maced for a minor violation.

The most recent statistics show that fatal police killings are increasing — AND that Blacks and Hispanics feel the brunt of police killings more than any other group. The rate of police killings by gun among Blacks is 35 per million; among Hispanics, 26 per million. Among whites, the rate is only 14 per million. In fact, the rate of police killings of Blacks hasn’t changed in at least five years, says Yale News: today, just like 2015, Blacks are almost three times as likely to die in police shootings as whites.

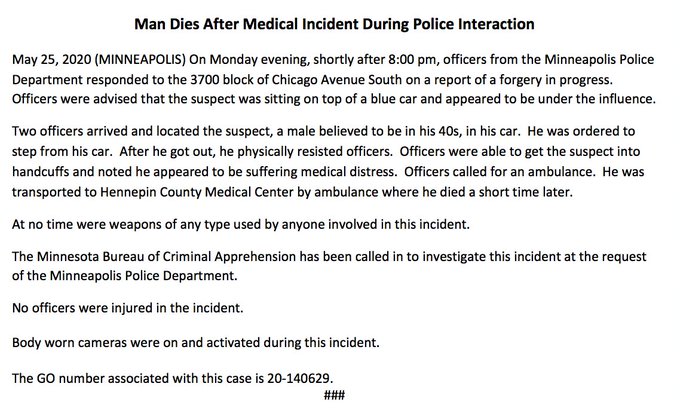

Immediately after the Chauvin verdict, many media circulated the initial police report on Floyd’s murder, filed by the police department in June 2020 before that horrendous video went viral. The initial report, eventually proven false by omission, reads like scores of other police reports. It is dotted with sanitized language indicating vaguely that Floyd “appeared to be under the influence,” “physically resisted,” “appeared to be suffering medical distress,” and “died a short time later.” The standard CYA (“cover your ass”) phrasings were also inserted: no weapons were used, body cams were on, an investigation is forthcoming.

That document, re-released, rattled us back to reality. Chauvin wasn’t the only cop who initially thought he could get away with the torturous murder of Floyd. A whole department thought he could, and made itself complicit by telling lies of omission.

In other words, the Chauvin case is also a clear illustration of the need for “system-wide reform.” It’s a starting point, not an end point. It’s why we need to keep exploring the police. Because clearly, as that document illustrates in black and white, we still can’t trust ’em, the collective “them.” How can we respect police if police think they’re above the law they enforce on others?

Solutions are urgently needed; but first, the real problems need to be acknowledged:

BAD RELATIONSHIPPING AS POLICE TACTICS: LYING AND ABUSIVE LANGUAGE

No one would disagree that if you lie to someone repeatedly, you lose their trust, and furthermore, you’ll eventually lose that relationship. Another common lesson of relationships: if your standard is shouting, cursing and profanity — especially during times of stress — that too will chip away at that relationship over time.

Yet, lying is a part of cops and detective work: if you’re an officer, under many circumstances, you’re empowered to lie to someone to lure them to rat on someone else, to position yourself under a fake identity as a witness of illegal behavior, to trick someone into confessing. Likewise, video after video of police interactions gone bad feature profane blasts from the enforcer of the law. Whether it’s the cop who first stopped George Floyd, or the cops who threatened the lieutenant out of his car, or the cop who shot 13-year-old Adam, or so many other police … hyperbolic language often seems pulled straight out of a movie.

In some cases, this is actually literal: The officer who stopped Army Officer Nazario shouted, “You’re fixin’ to ride the lightning, son,” a reference to death by electrocution most famously referenced in the movie “The Green Mile.” “xxxxx the fuck xxxx,” seems to be a favorite sentence construct for far too many cops. It’s as though profanity, and in particular THAT profane word, is considered a verbal weapon, a way to demonstrate that you’re playing the role to the max.

Why have we become so comfortable with cops lying to us? Or cursing at us? Why aren’t we asking these questions before now? Why do Black people have to die daily on video for us to finally ask these basic “questions of decency” of police?

A deeper question, hinted at by the increased domestic violence among police officers: what makes us believe cops who are told it’s OK to lie, curse and scream on the job will simply turn these instincts off when they’re not appropriate? Are they super-human, somehow immune from the basic human instincts that us mere non-cops have to work on after “merely” sitting at a desk job all day, doing manual labor in the sun, or waiting tables for hours?

That’s ridiculous: if you get used to lying, you start to think lying is OK, cop or not. If you start leaning on swearing and cursing and threatening as a way to get what you want, you start swearing and cursing and threatening more, to get what you want. Cop or not. Cuz we’re all human. But there’s a reason we let cops get away with this behavior.

POLICING AS ENTERTAINMENT

When the late great Chadwick Boseman passed away, I went on a search to view his most-heralded movies. Among them was “21 Bridges.” “An embattled NYPD detective is thrust into a citywide manhunt for a pair of cop killers after uncovering a massive and unexpected conspiracy.” I actually had to try three times to watch the movie, because in the context of George Floyd’s murder, it felt wrong watching a Black man star in a movie that was still built around glorifying the police.

Truth be told, it’s almost impossible to find a thrill-action movie or a television drama that doesn’t glorify cops. “Police protagonists have long been a staple of movies and TV, stretching back to James Cagney’s righteous FBI agent in 1935’s “G” Men to the ’60s series Dragnet to today’s police procedurals (dubbed “copaganda” by critics),” wrote Hollywood Reporter in July 2020.

The trend isn’t stopping: “The original Law & Order has spawned five spinoffs including SVU, which was recently renewed for its 22nd, 23rd and 24th seasons, as well as a TV movie and five video games,” Hollywood Reporter continued. “And the buddy cop movie continues to rack up billions at the box office. The Bruce Willis-led Die Hard franchise earned $1.44 billion worldwide, and the genre shows no signs of abating, with this year’s Will Smith-Martin Lawrence pairing Bad Boys for Life landing $419 million worldwide.”

We as consumers have willingly fed decades and decades of Hollywood figuring out how to jack up the thrills, all the while furthering images of cops as glamorous, gritty, fighting the good fight, exposing themselves to danger, and deserving of our empathy and sympathy no matter what collateral damage they inflict. Imagine how any of those franchises would hold up if their main plot line featured people speaking politely to each other about solving problems and leaning on conflict resolution tactics, rather than pulling guns and shouting dramatic profanities.

But it’s never just Hollywood.

GUNS AND GUN POLICING

The warrant on which police stopped Daunte Wright before shooting him dead involved charges he and others used a gun during a home invasion. Another previous charge against him also involved gun possession. Suspicion of a gun, fear of a gun, mistaking something else for a gun, or previous gun charges are a common factor in many shootings.

If you are a gun control advocate pushing for tighter regulation of gun ownership, keep in mind that by doing so, you’re giving more power to the very cops whose over-comfort with guns is part of this epidemic of police brutality. More gun laws mean more interactions like the one that led to Wright’s death, more reasons for police to pull people over while they’re going about their daily business.

Though this MIGHT mean catching more potential mass shooters, it’s not likely: all the recent mass shooters obtained their firearms legally. It definitely means more confrontations with police.

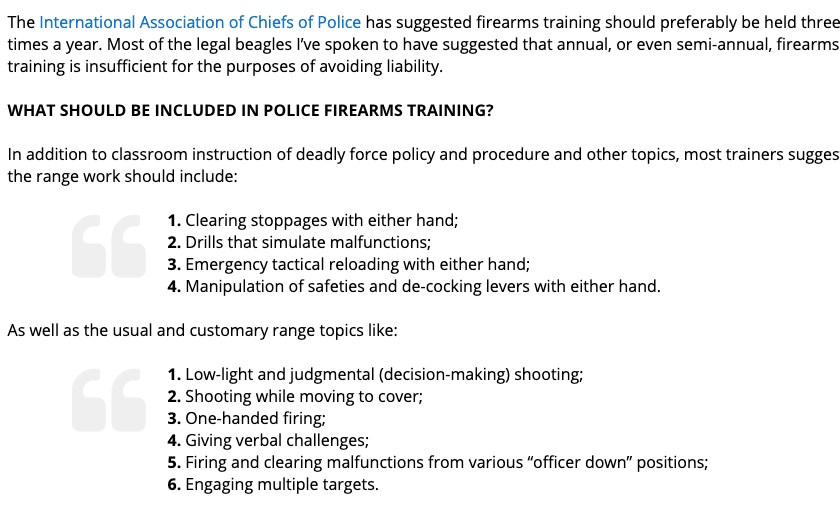

Not to mention, we are way too comfortable giving too much gun power to police, whose firearms training is actually shockingly minimal. On average, reports use of force expert Dave Grossi in a 2017 article, police departments undergo firearms training as a group only once or twice a year, for a total of 15 hours annually. This is less time than I spend mowing my lawn each summer.

This same article also provides a glimpse into what officers are learning during these precious few hours each year during “groupthink on firearms.” They are NOT learning how to minimize harm, how to avoid using a firearm, how to lessen the role of firearms in conflict. The bullet points on what they’re learning to do with bullets are about improving their vantage point as the shooter. From the start, throughout their careers, and especially while gathered as a group, our police officers are learning a one-sided view of the gun in their hands.

The recent rash of police shootings, and guns as the over-simplified solution for law enforcement, demands we change the way police view guns — not increase their control over everyone else’s guns. But there’s more to be done.

DRUGS AND DRUG POLICING

Chauvin cited George Floyd’s suspected drug use as justification for his deadly positioning on top of him. Wright had at least one marijuana-related charge on his record (although contrary to early rumors, it was unrelated to the stop that day). The father of 10 gunned down Wednesday morning was being served a warrant on drug charges. Suspicion of carrying drugs, previous charges for carrying or using drugs, or concern that someone is extra dangerous because they’re under the influence of drugs are all common “pretexts” cops cite for their harsh treatment of Blacks and People of Color.

But the whole demonization of drugs isn’t so simple anymore. Cannabis is now legal to some degree throughout most of the country, and legalization is one of the few issues with agreement across party lines. Columbia researcher Carl Hart revealed he’s been micro-dosing with heroin for years and lobbies for its positive effects. Psychedelics are considered to be useful in treating some mental health conditions. And a physical dependence on opioids — what we’ve grown too comfortable calling “addicted” — is now recognized as unavoidable with consistent use of these too-popular pain relievers, that are also sometimes medically necessary for a rare few.

“Drugs” are no longer an acceptable reason to stigmatize anyone — especially considering how we still glorify one of the most toxic drugs ever, alcohol. Without drugs as an easy tool at hand to demonize People of Color, police have to use real tools. Like good communication, human empathy, a better understanding of cultural experiences different than one’s own, and psychological assessments and insight. Changing our drug policy and our whole attitude toward drugs may be the most door-opening change we can make.

PRETEXTUAL STOPS: WHERE IT ALL COMES TOGETHER

Drugs and guns, and police tactics to enforce laws that control or prohibit them, are the main factors behind “pretextual stops” like the one that led to Daunte Wright’s killing. Cops stopped him because of some minor infraction over something hanging from his windshield. But the real reason they stopped him: a warrant issued when he didn’t appear for his Zoom hearing over previous gun possession charges.

Pretextual stops are yet another way we allow police to fib, and operate under false pretense — things that will hurt almost every other type of relationship that exists. The U.S. Supreme Court reconfirmed their legality in 2018. One study showed that 70 percent of such stops involved Black drivers. Thankfully, pretextual stops are getting a second look yet again though a Supreme Court reversal is unlikely any time soon, without a rash of court challenges. They are just one element of the deadly stew of inappropriate policing and police brutality.

DEFUND POLICE? BETTER, FASTER SOLUTIONS EXIST

We all want our police officers overall to either function with greater compassion, respect for life, and sense of service — or go away. With the rash of recent video killings of unarmed Black people, calls for police to just go away have flared anew. Yet, that’s not what the vast majority of Americans actually want; a July 2020 Gallup Poll showed only 15 percent of all Americans supported getting rid of police altogether, reports CBS News. It’s also not what some Black Lives Matter pioneers want: opponents to defunding include Sybrina Fulton (mother of Trayvon Martin), and the Rev. Harriet Walden, a Seattle activist who leads the group Mothers for Police Accountability, reports the Guardian.

Statistics also show that we are currently in an explosion of violent crime nationwide that has been happening for three years; studies show homicides in particular grew from 34 to 85 percent in different cities from 2019 to 2020, reports Salon. This means slashing police funding right now would be mired in a blame-game that will only slow true change and trigger more ideological clashes.

Not to mention, we’re not yet ready to “defund” police: though transferring funds to social workers sounds great on the surface, it’s impossible when you realize that there are already drastically fewer social workers than police, reports CBS News.

Of all the steps needed, defunding should be last on our list. So many other steps can have a faster impact, without the divisive debate, political campaigning and questionable impact.

• Tackle overzealous outdated drug and gun policies to decrease the likelihood of police encounters in the first place.

• Immediately upgrade firearms training for police to be more frequent, lengthier, and to focus on minimizing harm rather than merely ending a threat.

• Reinstate the common sense of truth, honesty and basic mutual respect in police codes, in police training, in police staff meetings. Common sense tells us an officer forced through training to think more about their words before speaking or shouting will likely begin immediately to think more about their actions, too — like shooting guns, suffocating someone, or wielding other deadly force.

THE MOST OBVIOUS SOLUTION OF ALL: DIRECT ACCOUNTABILITY

All of these solutions — and even defunding — remain weakened until we tackle the “you scratch my back, I’ll scratch yours” world in which police officers operate: the world of qualified immunity. It’s the key point of difference right now at the federal level in negotiations over the George Floyd Justice in Policing Act.

The official explanation of qualified immunity is that individual government officials are personally liable only for clear constitutional violations. In reality, however, “qualified immunity” essentially leaves taxpayers more liable for officers’ actions than the officers themselves. “it is nearly impossible to hold law enforcement officers accountable for even the most serious and deliberate violation of constitutional rights,” writes Pacifica Legal. “Courts will not impose liability unless virtually identical conduct has been the subject of a past lawsuit and was declared unconstitutional. And since immunity from suit prevents constitutional violations from becoming “clearly established” in the first place, qualified immunity creates a cycle that frustrates the enforcement of constitutional rights.”

This means officers function every day with an extra level of “not my problem.” Rather, they know it’s the goverment’s problem. Taxpayer-funded governments end up focusing on protecting themselves from litigation rather than cleaning up bad behavior. Like a family steeped in abuse, It’s a veiled, dysfunctional cycle in which an unhealthy cross-section of selfish interests leads to personal responsibility disappearing from the discussion, and bad patterns entrenching as “normal.”

Qualified immunity, as one of my mentors counseled me, spreads like a raging virus among the courts system, public defenders, probation officers, political campaigning, and media coverage. All those institutions join in that artificial environment of “not my problem.” Ending qualified immunity is like a mass systemwide intervention, finally taking off the blinders, and letting things hit rock bottom. collectively and individually, so we can rebuild fully. It’s the heart of the issue.

In closing, simple solutions never exist. We all need to delve in to the deep and real solutions. Progressives need to rethink some policies, even as we’re asking conservatives to rethink THEIR stances. We’re all part of the problems and answers: individual cops, every single governmental institution, lawmakers, Hollywood and its consumers, party leaders, party members, and the independent or nonpolitical. And the solutions aren’t ideological.

They’re basic decency, common sense, and good relationshipping. Even for cops.

Christine Hawes is founder and editor of The Real MainStream. Contact her at 319-777-9839 or chris@therealmainstream.com.