Before Stonewall, there was the gay purge. It happened at universities across the country, mostly targeting gay male students and professors, as far as any reports know..

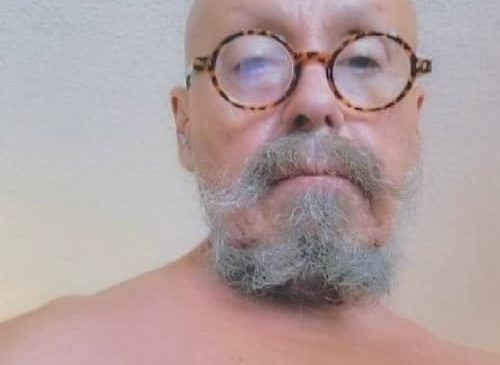

The University of Northern Iowa is one of the few universities nationwide that have publicly acknowledged and made amends for what was essentially a witch hunt for gay men in 1965. Timothy Sullivan, a native of tiny West Union who now lives in Palm Springs, Ca., is currently the only publicly known victim of that purge still living.

Sullivan eventually labeled that painful rejection as “the best thing that ever happened to me” because it propelled him to an illustrious career in his favorite things, art and fashion. And UNI issued a formal apology to Sullivan along with a special campus visit in October 2019.

But the “gay purge” offers so many lessons for today, as new morality wars heighten to frantic, confrontational and even violent levels.

Other state universities that had documented “gay purges” include Texas, Missouri and Wisconsin in the 1940s and 1950s, reports the History of Education Quarterly. Sullivan says he believed the effort at UNI was driven by fears of gay men becoming teachers (UNI was, at that time, exclusively for aspiring teachers).

This pattern of gay purges also happened in the 1950s among public officials, reports The History Channel. Gay public servants were increasingly labelled “unfit to serve.” Many gay men and lesbians were dispelled from the military during World War II, says the National WWII Museum in new Orleans.

Sullivan, now 77, remembers receiving a letter from the university informing him that he was expelled because one of his friends had reported him undertaking sexually deviant behavior. He never learned who reported him, or to whom.

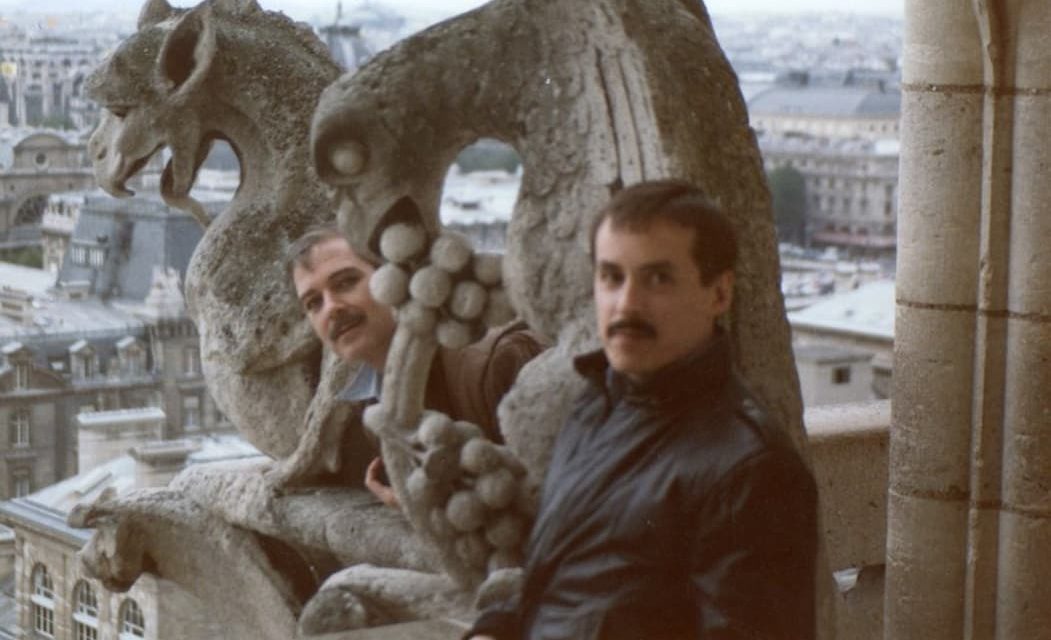

Instead, he took off for California almost immediately, then moved to New York City, all the while building a vast career in visual merchandising with clothiers that eventually included Levi-Strauss & Co. and Brooks Brothers. Sullivan also found his lifelong lover in 1977, and the two travelled to Cedar Falls in 2019 to receive an apology from then-Vice President Paula Knudson.

While being interviewed on the phone from his current home in “The District” neighborhood of Palm Springs, Sullivan hardly dwelled on being “purged.” Instead, he focused almost entirely on his fond memories of his career and life since, and about growing up openly effeminate in northeast Iowa’s West Union.

Only about 225 people lived in West Union at the time, Sullivan recalled. Everyone knew everyone, he said, and he had no hesitation about expressing his full self asa child. He openly played with dolls, a preference his parents respected.

He spurned anything having to do with sports, remembers his brother Terry, a retired teacher and coach in Davenport public schools. Terry also remembers that his brother ws the first teenage boy in town to wear short pants.

Yet, Terry says, his brother only formally told him he was “gay” in the early 1970s. And Tim only told Terry about being kicked out of college because of it decades later, in the late 1990s.

“I didn’t have a word for it at the time,” Tim Sullivan says, explaining why he never came out as “gay” to his family yet always felt supported for who he is. Tim remembers attaching the word “gay” to himself when he heard a snide radio commentator joke that you could spot gay men because of their Italian loafers and puffy sweaters. “I remember it so clearly,” Sullivan says. “I remember thinking, ‘wait a minute, I like Italian loafers, and I wear puffy sweaters. I’m gay!’ “

Tim Sullivan began actually asking his parents for adult dolls and rejected anything sporty, his brother remembers. Tim acted out his early love of art and fashion by designing hoop skirts and puffy, dramatic dresses for all of his dolls.

His lover passed away of dementia in 2021, Sullivan said, after a 40-year relationship that befriending movie executives, living in Paris, and lots of travel. Sullivan said he is still touched by his return to UNI in 2019, which came about only because his brother brought up Tim’s expulsion to a college executive in 2019.

While attending UNI’s Golden Anniversary celebration, Terry Sullivan said, he mentioned to former UNI official Lisa Baronio that his brother should have been there, too. Tim would have graduated one year later than Terry if he hadn’t been expelled for being gay.

Baronio, who is now head of the Veterans of Foreign Wars Foundation, set about researching the situation and at first couldn’t evene locate a record of Tim Sullivan, his brother said. Eventually, Baronio’s investigtaion led to the 2019 ceremony and apology.

Leslie Prideaux, editor of the Alumni Magazine that covered the event at the time, said the whole experience helps illustrate the importance of honoring the experiences of those who suffered before us.

“I feel like any time you recognize a wrong and own it, you are not only clearing a path forward, but you’re also honoring those who came in the past.and who struggled in the past,” she said. “And it’s really important for us to recognize the struggle of members of the LGBTQ+ community. I think it helps our current students understand how far we’ve come but also to recognize how much farther we need to go.… you can’t take things for granted.” ▪