This is a case of a lesson learned, and then unlearned.

Some years ago, as a high school art teacher, I learned to withhold praise for personal styles in student work. Teens, not fully formed in mind or body, will stay with the praised style, hesitant to explore other ways of working.

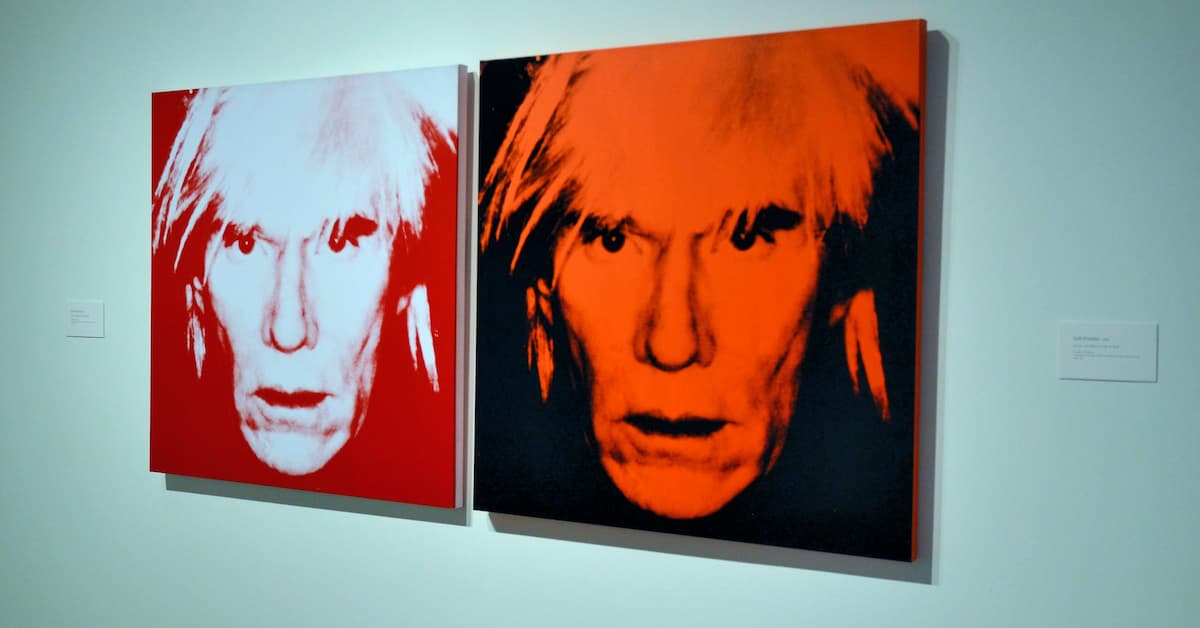

Andy Warhol embodied this behavior.

TEEN WARHOL

Hyperallergic Magazine reported on teen art at NY’s Metropolitan Museum of Art, a display of students who had won this year’s 90-year-old Scholastic Art Awards. The magazine mentioned that Warhol won the same award in 1945, when he was 17.

As it turned out, what you saw back then is what you got from Warhol forever after: copying. The Magazine Antiques described his teen work in a 2015 article, outlining numerous instances of appropriation evident in a newly-discovered collection of Warhol’s early work.

The article describes Warhol’s teenage depictions of his hometown of Pittsburgh, suggesting he took many of his images from newspapers or magazines, calling it evidence of “Warhol’s lifelong practices.” His latter-day soup cans, Coke bottles, and Brillo boxes make the point.

IN CONTRADICTION

All that said, I nevertheless write today to praise one of the teens’ works on display at the Met: a black and white untitled photograph by 11th grader Dylan Kelly. (More on reasons why in a moment)

The Met reported that 250 teen works were picked to hang in its galleries out of 2,500 who submitted work in the 2021 Scholastic Art Awards.

I rush to say that my choice to highlight Dylan in no way reflects badly on the remaining winners. This is a good place to add that competition in school children’s artwork is a terrible idea. School is a time for finding things out, not defeating fellow students. Art-making isn’t a sports event.

DYLAN KELLY’S PIECE

Dylan’s photo, a spectacular elevated long shot taken from an upper-floor window, shows an Orthodox Jewish father and his son walking on a city street at night.

The ethnic identity is apparent in the telltale long curl of hair coming from the father’s sideburn, the long black coat, and hat. But the ethnicity of these figures can just as easily be a Black father with his child. Both Jews and African Americans suffer hate crimes, and there’s a palpable sense of impending doom here.

When Dylan pulled back to shoot the scene, he created the portentous air. His zooming out and up also makes father and son smaller, even approaching insignificance. Dylan gets a lot in this shot, which conjures up Alfred Hitchcock films. I’m thinking of the way this 11th-grader manipulated viewer reaction with odd angles – a signature of the movie director’s work. Dylan’s detached long view is a poignant commentary on alienation, and intensifies the emotion of the scene.

ALIENATION AND THE PRINCE OF POP

Of course, when it comes to talk of alienation, no one intensifies a sense of estrangement better than Warhol. You can’t talk about indifference without mentioning the “Prince of Pop.” Think of how he callously squared his wallpaper-like soup can paintings with Jackie Kennedy in bloodied pillbox hat. The sheer repetition of her grieving served to numb perception. Or as he said in an interview with Art News in 1963, “when you see a gruesome picture over and over again, it really doesn’t have any effect.”

He mindlessly went after this numbing result whenever he pictured gritty things — like electric chairs, car crashes, and shootings. It didn’t matter what disaster he pictured. He gave it all a feeling of withdrawal and remoteness.

And here’s the thing. He was proud of his disaffection. He wore it on his face with its perpetual blank television stare. He even spelled it out in an exhibit catalog for his 1968 show in Stockholm: “If you want to know all about Andy Warhol, just look at the surface of my paintings… and there I am. There’s nothing behind it.”

Unaccountably, though, the art world never gave a damn that he was so damn uncaring. In the Biennial 2000 at the Pennsylvanian Academy of the Fine Arts, curator Jonathan Binstock called Warhol “a passionate social observer.” Good thing he’s not around anymore. Can you imagine what he’d do with the George Floyd murder?

QUESTION FOR THE AGES

Given such senselessness, it’s unseemly to bring Dylan’s work back into the conversation. But the power of his photograph breaks through the Warhol hogwash.

The way he framed the shot with light that casts long deep shadows behind the figures, and at the same time illuminates them with light shining ahead of them…. Clearly, he wants us to worry about the father and son in a city street at night.

His photograph appears to ask us, will the pair be able to get to the lighted part of the street without harm?